Overview

Today it’s difficult to imagine a time when architects, intellectuals and even politicians could be passionate about social housing.

In the words of Russian émigré architect, Berthold Lubetkin – ‘nothing is too good for ordinary people’. Lubetkin was the main champion of modernism in mid-20th century Britain, but another less well known modernist architect who also embraced the use of new technology, materials and engineering, was Joseph Boshier.

I first came across Boshier in the late seventies when I was an art student. An article in an obscure architectural journal revealed Boshier as not only an intriguing character, but an inventive architect. I loved the clean cut look of his buildings. Later I was to find he had been a member of the British Union of Fascists – the feeling of disappointment was tangible.

Caught up in the heady politics of the thirties, Boshier joined forces with his aristocratic wife’s friend Oswald Mosley. When they met, Mosley was in the Labour government and both men advocated Keynsian economics as a way out of depression and poverty – both supported a united Ireland. After the horrors of the war, Boshier wrote of his friendship with Mosley and his charisma with a venom.

Boshier’s life spans a period when there was a belief in social housing – that there should be an end to slums and draconian landlords and good affordable housing for all. It’s interesting that Boshier died at the time of the Falklands campaign, an event that would strengthen a government dedicated to the demise of social housing.

– Lesley Hilling

Biography

Joseph Harold Boshier was born June 25th 1898 into a comfortable middle class home. His father Harold Boshier was a bank manager who in 1896 married Nuala Bell, a governess working for the family of one of Harold’s old school friends. Joseph’s childhood was idyllic. Like his father before him, Joseph attended Dulwich College the exclusive boys school in South London near their home in Herne Hill.

In 1917, three years into the great war, Joseph joined the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. Fighting in Palestine at the Battle of Gaza, he was injured and spent the rest of the war recuperating in Scotland. Two years after the war he travelled to Europe spending time particularly in Rome, Berlin and Paris, immersing himself in the new art and architectural ideas of the time. In Paris he met Auguste Perret and his brother Gustave and became interested in building with concrete. He also met Le Corbusier and Lubetkin who both studied with Perret. These years in Europe informed his later life as an architect. Between 1922 and 1923 he worked with Gustave Perret on the church of Notre Dame du Raincy in Le Raincy France. Unfortunately this was cut short when Joseph was called back to London because his father was gravely ill. Harold Boshier died shortly after and Joseph stayed on at the family home in Herne Hill. Following his desire to become an architect, Joseph Boshier enrolled at the Architectural Association in 1924 where he studied for the next four years. Here he met the young Valentine Harding, who was to become his close friend.

During the General strike in 1926, Joseph, anti communist and already quite right-wing, volunteered to drive a London Bus. He met Mildred Haviland, one time suffragette and fellow volunteer, who was serving tea in a London Transport canteen. Mildred came from an aristocratic family, the daughter of James Herbert Haviland whose family owned vast tracts of land in Berkshire. She was a well known society hostess, married to building magnate John Dawson, she was in the process of a well publicised divorce. Mildred and Joseph fell in love. In 1930 Joseph and Mildred married and after selling the family home they moved to Dulwich. Through Mildred, Boshier met rich socialites interested in small architectural commissions and in 1928 he sets up his own practice called Gerda. Small commissions for the rich – Joseph saw this as a start to his career but it wasn’t the work he really wanted to do.

Mildred was an intellectual and introduced Joseph to many important thinkers of the time, most importantly Oswald Mosley, who at that time was the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in the Labour government. Both men were interested in the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes and in 1931 when Mosley, disillusioned with the Labour party sets up the New Party, both Mildred and Joseph join.

Other supporters included John Strachey, Mary Richardson, John Becket and Harold Nicholson. In the 1931 General election, none of the New Party’s candidates were elected. Mosley disbanded the New Party and after seeing Mussolini in Italy formed the British Union of Fascists. Joseph and Mildred both joined the BUF.

Between 1932 and 1933 Joseph worked with his old friend Val Harding on Six Pillars in Crescent Wood Road, Dulwich. Although both men shared the same modernist principles their relationship was severely strained by Joseph’s growing involvement with the BUF and in November 1933 Joseph left to concentrate on his own practice. However, upset by the growing anti-Semitic views of the BUF, Mildred and Joseph’s involvement declined and in 1935 they ended their association with the British Union of Fascists totally.

Tragically in late 1935, a fire engulfed their Dulwich home and both Joseph’s mother and pregnant wife were killed. A devastated Joseph stopped work to grieve. The guilt he felt for this enormous loss had a great impact on his mental state. Joseph renewed his friendship with Val Harding, now working at Bertold Lubetkin’s practise Tecton; with his support Joseph was able to re-establish his own practice and in 1937 began work on Chesney Court, a ten storey concrete structure built in the modernist style. Situated in a working class area of South London, it aimed to house factory and shop workers from The Elephant And Castle area. Politically and artistically it fulfilled the ideas Joseph had been working toward and when it was completed in December 1938 it was acclaimed as a superb modernist building rivalled only by Lubetkin’s High Point One.

After the great success of Chesney Court Joseph’s practice flourished and in late 1938 he married Alma Nevelson, a friend of Valentine Harding. She was fifteen years his junior, studying music and working toward becoming a concert pianist.

After the great success of Chesney Court Joseph’s practice flourished and in late 1938 he married Alma Nevelson, a friend of Valentine Harding. She was fifteen years his junior, studying music and working toward becoming a concert pianist.

At the outbreak of war in 1939 Joseph was threatened with prison for his involvement with the British Union of Fascists and the popular press questioned his loyalty. Sadly once again a devasted Joseph was forced to close his practice. Tired and disillusioned he joined the staff at the Architectural Association, where he stayed until 1947. Early in 1948 the child Joseph and Alma longed for was born, a daughter christened Constance.

On September 29th 1948 the first two floors of Chesney Court buckled and the ten storey concrete structure collapsed leaving three dead and forty seven injured. Joseph, devastated, goes into hiding until the subsequent enquiry a year later. Joseph was exonerated but the press continued to vilify him, raking up his BUF past. Racked with guilt he has a nervous breakdown and spends three months in The Maudsley Hospital. On his return home Joseph and Alma struggle to keep their marriage but in 1951 Alma and Constance finally leave. Joseph will never see either of them again. Under great mental strain and unable to work, Joseph sold the family home and moved to a smaller property in Camberwell where he lived for the rest of his life.

Joseph Boshier disappeared from the architectural scene and was forgotten. Alone and reclusive his only human contact was his neighbour Augusta Hodges and the occasional visit from the Social Services. In 1980 he was approached by student Derval Tubridy who was writing a thesis on British architecture in the thirties. At first reticent Joseph reluctantly agreed to meet Tubridy and they became friends.

Joseph Boshier died on February 10th 1982.

His daughter Constance, named as his sole beneficiary finds a father she had believed died in 1948. On entering his Camberwell abode she finds a staggering trove of intricate wooden sculptures and a mass of drawings and writings.

The reclusive artist

On his death in 1982 his south London home revealed a staggering trove of intricate wooden sculptures and a mass of drawings and writings. Labyrinthine, oppressive, dark, narrow and magical, his home was stuffed full of collected artefacts and ephemera. The once revered and public figure had retreated into a self imposed exile, solidifying his existence in his small terraced house in Camberwell.

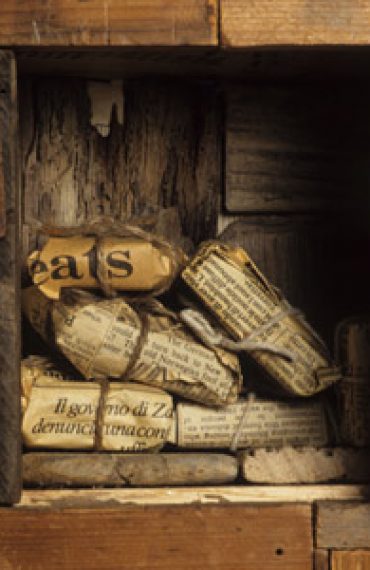

Subsisting for decades on a tiny income, he had produced a series of extraordinary sculptures, collaging new forms out of salvaged wood – often using his own floorboards and furniture and re-working them with an obsessive joinery. His largest piece echoes the L shape structure of Chesney Court but also resembles a curiosity cabinet or old fashioned front room sideboard.

These works are not architectural models of Chesney Court but perhaps an exploration of the lives lived within and an expression of the guilt and loss felt by the architect. A fretwork of wooden pieces built up in layers allows glimpses of what lies within – artefacts and ephemera that Joseph may have held dear, although thus far the photographs have not been identified as any of those killed in the disaster. In a sense he lifted the roof off a block of flats and showed how people transform their homes and create meaning for themselves and their own history within it. Perhaps they speak to us of our own mortality.

On his death in 1982 his south London home revealed a staggering trove of intricate wooden sculptures and a mass of drawings and writings. Labyrinthine, oppressive, dark, narrow and magical, his home was stuffed full of collected artefacts and ephemera. The once revered and public figure had retreated into a self imposed exile, solidifying his existence in his small terraced house in Camberwell.

Subsisting for decades on a tiny income, he had produced a series of extraordinary sculptures, collaging new forms out of salvaged wood – often using his own floorboards and furniture and re-working them with an obsessive joinery. His largest piece echoes the L shape structure of Chesney Court but also resembles a curiosity cabinet or old fashioned front room sideboard.

These works are not architectural models of Chesney Court but perhaps an exploration of the lives lived within and an expression of the guilt and loss felt by the architect. A fretwork of wooden pieces built up in layers allows glimpses of what lies within – artefacts and ephemera that Joseph may have held dear, although thus far the photographs have not been identified as any of those killed in the disaster. In a sense he lifted the roof off a block of flats and showed how people transform their homes and create meaning for themselves and their own history within it. Perhaps they speak to us of our own mortality.

A Documentary Film

On September 29th 1948 the first two floors of Chesney Court buckled and the ten storey concrete structure collapsed leaving three dead and forty seven injured. Ten years earlier the building was proclaimed as a breakthrough in design and construction, the collapse of the building shook the architectural world and the public at large.

Although the subsequent inquiry could find no obvious reason for the disaster, the press singled out the architect, Joseph Boshier for blame. Joseph Boshier was a successful London architect with several impressive projects behind him – now his career was in ruins. After a nervous breakdown and estrangement from his wife and child Joseph became a virtual recluse. He disappeared from the architectural scene and was forgotten. On his death in 1982 his north London home revealed a staggering trove of intricate wooden sculptures and a mass of drawings and writings.

Subsisting for decades on a tiny income, he had produced a series of extraordinary sculptures, collaging new forms out of salvaged wood – often using his own floorboards and furniture and re-working them with an obsessive joinery. His largest piece echoes the L shape structure of Chesney Court but also resembles a curiosity cabinet or old fashioned front room sideboard. These works are not architectural models of Chesney Court but perhaps an exploration of the lives lived within and an expression of the guilt and loss felt by the architect. A fretwork of wooden pieces built up in layers allows glimpses of what lies within – artifacts and ephemera that Joseph may have held dear, although thus far the photographs have not been identified as any of those killed in the disaster. In a sense he lifted the roof off a block of flats and showed how people transform their homes and create meaning for themselves and their own history within it. Perhaps they speak to us of our own mortality.

This film is a personal journey for Dr Derval Tubridy – in the role of architectural and cultural commentator, she was a friend and correspondent of Boshier’s toward the end of his life. She will introduce the viewer to him and narrate his story with the help of other people who knew Joseph and Paul Warner an expert on architecture.

The documentary features the voice and old footage of Boshier’s daughter, Constance Ripley who, sadly, is now deceased. In 1983 she gave a radio interview on Radio London talking candidly about the discovery of a father whom she had believed dead for most of her life. Constance also made super 8 films of the inside of Boshier’s Southwell Road house and catalogued his work.

Lesley Hilling presents

“Fiction enables us to grasp reality and at the same time that which is veiled by reality” – Marcel Broodthaars

The Joseph Boshier project came about because I felt my work looked very different to the work of more conceptual artists who were showing at the time.

The pieces looked as though they had been made in the nineteenthirties by an unknown artist anonymously beavering away in his cellar. Gradually that character turned into Joseph Boshier.

Somewhere along the way he became real to me and I began inventing a life for him. I’m a big fan of James Elroy and the way his books blur fact and fiction, so I started to weave Joseph Boshier’s world into twentieth century history.

Housing and architecture is important in my practise so Boshier became an architect. I have always admired and been influenced by the work of of outsider artists and the ability of art to heal and transform so that became an integral part of the story. He’s called Joseph after the legendary American artist Joseph Cornell and Boshier was my mother’s maiden name. There is an element of gender fluidity in the project, and all the pictures of Joseph are really me superimposed onto a picture of a celebrity from the thirties or forties. I also appear in the film as Boshier. All the players in the film are named after fictional characters in films and books who either don’t exist like George Kaplan in Hitchcock’s North By Northwest or characters who take on another identity like Tom Ripley in Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley books.

When I explained the idea to film makers Ivano Darra and Walter Graham Reed they were really excited and together we formed the Joseph Boshier Collective and began working toward an exhibition of Boshier’s work and a documentary film about his life.

The project took about two years to complete. We were lucky enough to have the support of Standpoint gallery in Hoxton, London. The exhibition took place in November 2013. I was able to borrow a lot of sold work back so the show looked like a real retrospective. The private view was one of the nicest evenings I’ve ever had. It was really well attended and there was a feeling of great anticipation as we all waited for the documentary film to be shown.

— Lesley Hilling

Fundraising

We financed the project ourselves. Our Indiegogo page raised £1060. We offered a variety of perks from credits on the film to an authentic box construction by Joseph Boshier – snapped up by our man in Los Angeles!

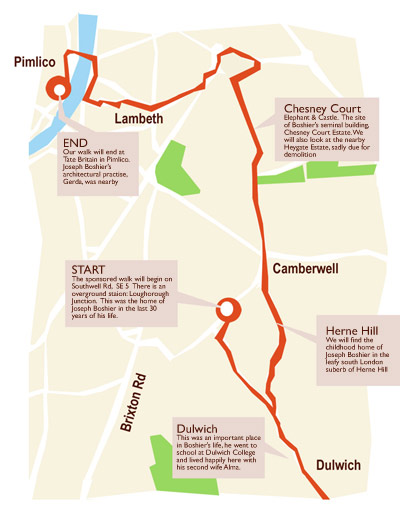

Our sponsored walk in July (on the hottest day of the year) raised over £300! The ten mile walk through south London took in all of the major Joseph Boshier landmarks from his school, Dulwich College to the site of his definitive building, Chesney Court. A big thanks to Rachel Hill for working out the route.

The comedy film night at Brixton Housing Co-op’s social club raised some more money to go toward our film. We showed Pedro Aldomovar’s Women On The Verge of A Nervous Breakdown and there were a lot of laughs, before the film we served vegetarian cuisine – but no gaspatchio!! Look out for our thriller night at BHCSC!

One of our best fundraisers was Joe’s Cafe – a pop up cafe in Brixton, happening over several weekends – we served all day breakfasts, vegetarian lunches and a selection of delicious cakes. We will definitely be doing Joe’s Cafe again – so follow Joe’s on Facebook!

And for those of you who missed it, here’s a short film.

The Joseph Boshier Collective devised a ten mile walk around south London that not only took in all the important sites of Boshier’s life but some of the most exciting architectural views in south London – from Dulwich College to the Heygate Estate.

The walk started at Southwell Road and proceeded to Dulwich College where Boshier went to school. Founded in 1619 by Edward Alleyn, the school is a beautiful building set in majesrtic grounds near to Dulwich park and Dulwich Picture Gallery. We also viewed the Headmaster of the college’s house, Six Pillars, a modernist building designed by Boshier’s friend, fellow architect Val Harding. Joseph also worked briefly on this building.

Then we went up toward the Elephant via Herne Hill where Joseph spent his childhood, sadly the house is no longer there but we saw the site and experienced the sleepy suburb of Boshier’s youth. It was one of the hottest days of the year, which made the scenery beautiful and the walkers hot and sweaty!

At the Elephant we stopped at the site of the Chesney Court Estate, near to the now empty Heygate Estate. Then we went on to our finish in Pimlico. This was the home of Boshier’s architectural practise, Gerda. We finished at Tate Britain for a much deserved cup of tea. An apt ending as of course, we feel Boshier’s artworks belong here.